Economists Richard Vedder and Lowell Gallaway contend that “the seven years from the autumn of 1922 to the autumn of 1929 were arguably the brightest period in the economic history of the United States.” This decade is often described as the “Roaring Twenties” or “Coolidge Prosperity” for the significant economic growth and entrepreneurship that occurred. It is also a decade of controversy, and many economists and historians continue to debate whether or not the seeds of the Great Depression were sown as a result of the reckless economic policies of the 1920s. Regardless, the economic evidence is clear that the 1920s represented an era of prosperity, which was the direct result of the conservative fiscal policies of Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Andrew Mellon, who served as Secretary of the Treasury in the administrations of Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover, led many of these policies.

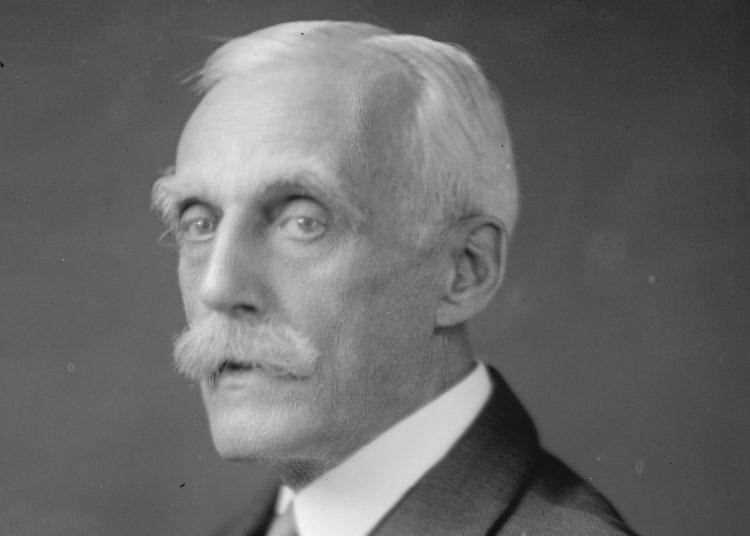

Andrew Mellon was described as the “greatest Secretary of the Treasury” since Alexander Hamilton. Mellon also admired Hamilton and his fiscal policies reflected the economic philosophy of our nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury. Prior to being selected by President Harding to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, Mellon was a successful financier and entrepreneur in Pennsylvania. Mellon engaged in steel and aluminum (Aluminum Company of America/Alcoa), among other industries. Mellon was also involved in banking, and just as with many other capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie, he also was a philanthropist.

Mellon’s experience as well as his political philosophy made him the strongest candidate to serve as Secretary of the Treasury. Mellon shared President Harding’s conservatism, which even included support for protective tariffs. In the presidential election of 1920, the nation elected Harding in a landslide. This was a rejection of President Woodrow Wilson’s internationalism and his progressive domestic policy agenda.

During the campaign Harding famously argued that America needed a return to “normalcy.” Harding’s “normalcy” agenda would become the foundation for economic policy during the 1920s. When the Harding administration assumed office, the nation was afflicted by a severe economic depression, which Vedder and Gallaway describe as the “most important business cycle development of the first three decades of the twentieth century.”

The economic depression of 1920-1921 is referred to as a “forgotten depression,” because it was short-lived, especially in comparison to the Great Depression. The national economy went into a “sharp economic downturn” that was marked by high unemployment that reached as high as 15 percent. Prices and incomes also declined sharply.

In approaching the economic crisis, President Harding called for a fiscal conservative agenda which included an emergency tariff, reducing government spending, lowering income tax rates, and paying down the national debt. Another part of the economic agenda included limiting immigration.

Mellon, as Secretary of the Treasury, would be instrumental in shaping and leading the Harding, and later Coolidge, economic program through Congress.

Mellon understood that lowering tax rates, reducing spending, and paying down the national debt were essential for creating an economic recovery.

Mellon outlined many of his economic ideas in his 1924 book, Taxation: The People’s Business. As a result of World War I income tax rates soared to as high as 77 percent on top incomes. Mellon argued that tax policy must take into consideration three main factors:

It must produce sufficient revenue for the government; it must lessen, so far as possible, the burden of taxation on those least able to bear it; and it must also remove those influences which might retard the continued steady development of business and industry on which, in the last analysis, so much of our prosperity depends.

Further, he argued that lower tax rates would discourage fraud and other tax avoidance strategies. In addition, lower tax rates would also encourage more revenue to be generated by the federal government. Although Mellon was not a supply-side economist, many adherents to this economic school of thought view him as a champion of their taxation theories.

Mellon, just as with Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, was a budget hawk, which meant that he believed in the necessity of a balanced budget. This is why even before cutting tax rates Mellon argued that spending must be reduced. Balancing the budget and payment of public debt, Mellon argued were “two guiding principles” that guided the administration. “It is the utmost importance that expenditures should be kept down to the minimum requirements of the government and that the budget should balance,” wrote Mellon.

The policy of reducing government spending, paying down the debt, reducing tax rates, and tariff reform were all pillars of the Republican economic policy agenda. After Harding’s unfortunate death in office, Coolidge would continue his economic agenda. Mellon and Coolidge shared a similar personality, and it was said that both “conversed in pauses,” because of their quiet nature.

As a result of Harding’s policies, the depression of 1920-1921 was resolved quickly and without a strong response from the federal government. Paul Johnson wrote that “this was the last time a major industrial power treated a recession by classic laissez-faire methods.”

Mellon was able to push through a series of Revenue Acts, which eventually reduced the top income tax rate from 77 percent to 24 percent. This was in addition to the conservative budgeting of the Harding and Coolidge administrations, which reduced spending and helped pay down the national debt. The federal budget, which had been just over $5 billion in 1921 was reduced to $3.3 billion by 1929 and the national debt was reduced from over $25 billion in 1920 to $16.9 billion in 1929. Congress also enacted legislation to limit immigration and passed the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act, which raised tariff rates.

The fiscal conservative policies led to a period of strong economic growth. Unemployment, which was as high as 15 percent in 1920-1921, averaged 3.3 percent from 1922 to 1929. Gross National Product (GNP) increased 7 percent each year as a result of the Harding and Coolidge policies.

The United States continued to be a manufacturing powerhouse with a 64 percent increase in output during the decade. As an example, the United States produced half of the world’s steel and manufacturing also led to consumer expansion with individuals purchasing automobiles and radios. Gene Smiley notes that “real per capita incomes rose by 2.13 percent per year.” This included both middle- and lower-income wage earners.

Michael Bernstein wrote that the “twenties were a period in which the American economy showed great health and maturity.” This is not to suggest that economic problems did not exist such as the crisis in agriculture and reckless behavior within the stock market. Nevertheless, fiscal conservative policies produced substantial pro-growth economic results.

In 1928, Mellon summarized the economic accomplishments of the Harding and Coolidge administrations when he stated:

Under the present administration taxes have been materially lowered on four occasions. Expenditures have been cut. The public debt has been reduced so that it is no longer a heavy burden on the taxpayers. The nation has been given the benefit of a protective tariff; and during the entire period the country has moved steadily forward, getting further and further away from the unsettled conditions which prevailed in 1921, when the present Republican administration took office.

Andrew Mellon helped shape a decade of economic policies that led the nation out of a severe depression and into an extended period of economic growth. Lawerance W. Reed noted that Mellon helped “foster a remarkable growth in productivity, investment, and innovation” during the 1920s. Mellon’s philosophy on taxation, government spending, debt, and even the tariff is still relevant and needed for today.