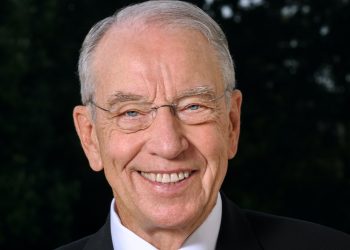

Editor’s note: The following is a transcript of a speech that U.S. Senator Grassley, R-Iowa, gave on the floor of the U.S. Senate on Thursday. You can watch the speech above.

I’ve come to the floor over the last few weeks to talk about the First Amendment, one of America’s most cherished pillars of freedom. Unfortunately, in recent years, we’ve seen a corrosive culture undermining sacred civic freedoms Americans risk taking for granted. Silencing the free exchange of ideas has infiltrated college campuses and the American workplace. It’s even affected journalism, in traditional media and across social media platforms.

We all know that not all speech is protected by the First Amendment. And occasionally, we in the United States fall into a discussion about the technical boundaries of the First Amendment when we talk about the meaning and merits of free speech.

The health of our democracy depends on free speech to foster an informed public. The rigorous exchange of ideas informs debate on issues affecting our lives, and enables individuals to challenge power and orthodoxy.

In theory, the institutions of the Fourth Estate should be the staunchest defenders of the First Amendment.

So it’s been baffling to watch over the last year as some editors and executives at storied institutions crumple under pressures to police speech, to conform to orthodoxy and to stifle the exchange of ideas instead of promoting the contest of them.

It’s now old news, but last summer a longtime opinion editor at The New York Times was pushed out for having the audacity to publish an opinion piece written by Sen. Tom Cotton.

Apparently a group of readers and employees found his ideas so upsetting as to warrant the removal of the editor who published them. The paper also issued a several-hundred word editor’s note to express regret for publishing the piece in the first place.

If those readers and employees at the Times disagreed so strongly, the public could have learned something by publishing a counter-argument, instead of reading about their regret. I myself have publicly disagreed with Senator Cotton about a policy idea or two, and I made my points here on the Senate floor.

Instead, we had executives at a paper of record scapegoat a colleague for failing to conform to some yet unexplained orthodoxy, versus the rational decision to engage in public debate on their own pages.

In January, Politico invited a slate of individuals to guest edit their widely-read newsletter, Playbook. Among those guest editors was Ben Shapiro, a conservative commentator.

His name alone was enough to spark a backlash among staffers and even outside commentators. To their credit, the editors at Politico did not apologize.

But according to the Washington Post media writer, some Politico employees who privately supported the choice to publish Shapiro were “afraid” to speak up on staff calls, fearing backlash among colleagues.

These episodes represent an unhealthy environment—where some think it’s prudent to give voice to those with whom they agree or whose views are deemed acceptable.

While the editors did the right thing at one outlet, they didn’t at the other. Either way, it probably means they’ll be more selective about what is “acceptable” in the future, which certainly doesn’t serve those principles I mentioned earlier.

These may be fairly obscure controversies, but they’re indicative of a wider problem. Expectations of “acceptability” and a preference for unchallenged ideas chip away at our most sacred civic freedoms in America.

No one learns more from less debate.

Neglecting to defend free speech and champion the free exchange of ideas creates a pathway for censorship.

The institutions of the news media ought to defend the fundamental principles behind free speech and free press at the top of their lungs. The First Amendment is the oxygen of their own existence.

Last fall, the New York Post had a story censored on Twitter a short time before the election.

Regardless of what one thinks about the content of that story, the methods of reporting, or even the tone of the writing, the suppression of information like that should alarm both news writers and news consumers.

Many outlets went to work fact checking or reporting on the topic in their own way. That’s all well and good. It’s their job.

But the public conversation about the censorship devolved into a question of whether Twitter had the legal ability to do what it did instead of a discussion of whether it was right to do it.

It wasn’t right. Even Twitter’s CEO sees that now.

However, there were no fiery defenses of free speech and free press from mainstream outlets. Not even ones with caveats about the reporting.

This was the perfect opportunity for journalistic institutions to weigh in. They have a dog in the fight. It should be the bread and butter issue for every editorial board across the country.

The lack of this kind of pro-free-press, pro-free-speech advocacy also contributes to the unhealthy environment that shuns debate and silences dissent.

So what will be the consequences of a media environment where conformity and comfort take precedence over the free exchange of ideas?

The first, and most obvious, is a less rigorous and less informed public discourse. Opinions and preferences, especially on matters of public interest, are always improved after being challenged.

If you disagree with the New York Times Editorial Board or a pundit on Fox News, that’s fine. It’d be better if the public heard all about it. Broader discussions mean broader understanding.

Without a broad, vigorous public debate, we lose empathy that results from engaging with someone else’s ideas. In these divisive times in society, empathy is in low supply.

The last thing we lose in a media environment ruled by compliance and conformity is the grand American tradition of dissent. Free speech and the free press have a centuries-long history in America. From Thomas Paine’s pamphlets to the tweets spreading across the land today, the revolutionary contest of ideas might take a different shape, but remains critical to our civic culture and continued growth as a nation.

I hope more institutions in the Fourth Estate will take a more aggressive approach advocating free speech. Now, I wasn’t around when Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” but history and my own experience teaches two important lessons: the free exchange of ideas strengthens representative government and will help preserve our democratic republic for generations to come.