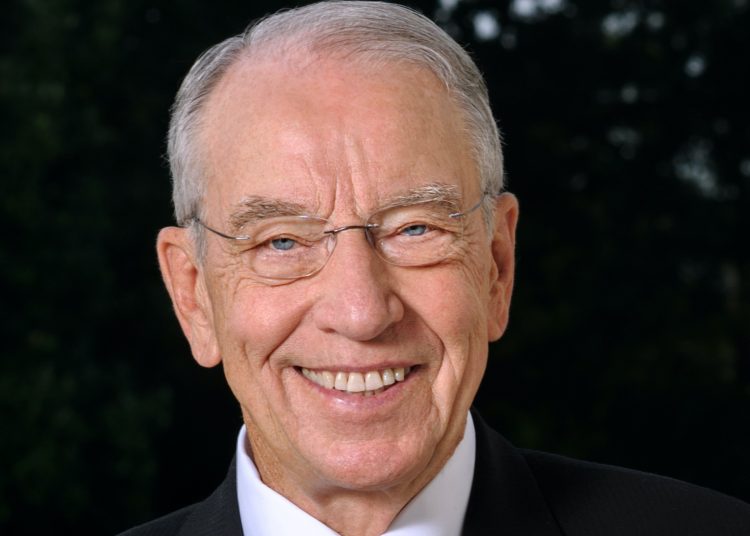

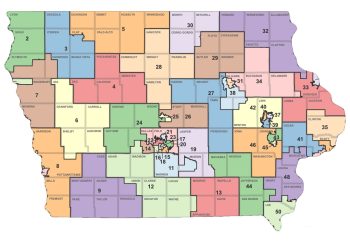

In January, I started my annual 99 county meetings across Iowa. For the last four decades, I’ve traveled to every corner of the state to hold open dialogue with my constituents. At my recent meeting in Delaware County in Manchester, I had a Q&A with workers who manufacture state-of-the-art snow plows, salt and sand spreaders and other types of equipment that help keep our roads safe during bad weather. We covered a variety of topics, including the pandemic.

The deadly coronavirus underscores why local health care services are a quality of life issue no matter your zip code, from testing, to patient care to vaccine distribution. Having a health care clinic in town also helps employers attract and retain employees, adds economic vitality to the community and gives peace of mind to residents who don’t have to travel an hour or more for urgent medical care, diagnostic and lab services or immunizations, for example. Manchester has a family health clinic designated as a Rural Health Clinic (RHC).

Congress passed the Rural Health Clinic Services Act in 1977 to increase access to primary care services in rural areas. Across the country, more than 4,100 clinics are designated as RHCs and receive extra Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement. Iowa has 197 rural health clinics. I made sure the pandemic-relief law enacted in December improved how Medicare pays RHCs so they can stay viable and thrive in their local communities.

During the pandemic, hospitals and clinics across the country faced substantial revenue losses as patients didn’t seek care and elective surgeries were cancelled or delayed while their costs increased to pay for personal protective equipment (PPP) and care for COVID-19 patients. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, which has legislative jurisdiction and oversight authority of federal health care programs, I’ve been a tireless advocate for rural health care providers and patients and work hard to serve as their voice at the policymaking table.

As Congress negotiated pandemic-relief packages throughout 2020, I championed increased financial assistance for rural hospitals and clinics and advocated for regulatory relief to give providers extra breathing room to keep their workforce on payroll and ensure they could keep their doors open during the pandemic and beyond. With the $900 billion pandemic-relief package enacted in December, more help is on the way. As Finance chairman, I pushed for an additional $3 billion to boost funding for rural providers, as well as increased flexibility for how providers can use the relief dollars they’ve previously received. I also secured additional flexibility for patients to have more control over their health with their Flexible Spending Accounts.

Access to emergency and primary health care services is a basic quality of life issue for a resident of any sized community. Because our rural hospitals, clinics, and physician offices are facing increased financial strain, it’s all the more important to ensure rural communities can maintain reasonable access to emergency and other medical services as close to home as possible.

The new law extends for three years important rural health provisions that would have expired on Dec. 31, including a boost in payments to physician practices. I also worked to ensure America’s vital network of hospitals and clinics in our rural health delivery system wasn’t left hanging in the wind. Our state has 81 Critical Access Hospitals and 47 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) providing care to Iowans. In addition to payment reforms for RHCs, the law establishes a new, voluntary Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) designation that offers financial support to struggling rural hospitals that can no longer support inpatient services.

Having led the charge to create a new, voluntary REH payment model since 2014, I’m very glad to get this designation across the finish line so that our devoted rural health care providers can keep offering essential medical services in their communities. The REH offers a financial lifeline for frontier providers by allowing certain rural hospitals to right-size their health care infrastructure and provide services that better align with the specific needs of their patient populations. As I often remind my fellow lawmakers in Washington, one-size-fits-all doesn’t always fit all and in too many cases leaves rural America behind.

Other key provisions extend the rural community hospital demonstration program for an additional five years, which gives payment certainty to several participating Iowa hospitals, and allow RHCs and FQHCs to provide and bill for hospice attending physician services when RHC and FQHC patients become terminally ill and elect the hospice benefit. This means that patients may continue to receive hospice-related care from their known RHC or FQHC primary care provider.

One silver lining of the pandemic became a golden opportunity to improve access to mental health care services in remote areas. Congress eliminated Medicare restrictions that will allow beneficiaries to receive mental health services through telehealth on a permanent basis. In addition, Medicare patients now will get better benefits for certain colorectal cancer screenings; kidney transplant patients may buy Medicare coverage to get prescription drugs needed to prevent a return to dialysis; and, Medicaid enrollees now may participate in clinical trials. During the 117th Congress, I’ll continue advocating for rural health policy to get us through the pandemic and beyond.